|

Here's the Excel file screenshot. All the light blue boxes (cells) are where you enter the needed info. The info for my 48cc crank is in there as an example. You can refer to my video on how to figure out equivalent balance holes for cranks with metal removed around the con rod pin area instead of holes. You will need a digital food scale and digital caliper. You can buy a scale at Amazon for $19 or one at WalMart for less. WalMart sells a digital caliper for $19 or you can buy one from Amazon for $23. This screenshot shows my balanced engine.  Notice the usage instructions starting at C44. First, enter all the necessary data in the light blue cells and click the "Graph V/H Forces" macro button to the right of the crank photo to display the vibratory forces throughout the RPM range in the graph starting at F1 (This isn't essential if your spreadsheet program can't use macros. In that case just type in the RPM you want to know about into E3. It's balance value will display at E45.) Then adjust the counter balance hole sizes (or add more holes or fill in holes) till the # at E45 is close to 0.97 (within .03). If it's more than ±3% then change the size of the balance holes accordingly. Click onto the macro button after every change to update the chart if you can use macros. If not then just go by the value at E45 which changes as you enter different info. If you are measuring where the current balance holes are and you want to calculate what the angle is between the hole and where the center of the con rod pin is then just measure the radius and the chord according to the picture below and use the angle calculator below K46 on the spreadsheet.   Any of four "hole sets" can be two or four holes each. If only two holes, they need to be at 0 or 180 degrees, aligned with the conrod pin. The example on the spreadsheet shows four holes 24.5 degrees from the conrod pin (set #1), two holes in line with the conrod pin (0 degrees, set #2), 2 holes opposite the conrod pin (180 degrees, set #3) drilled in from the exterior not the side, and two holes in line with the conrod pin (0 degrees, set #4) drilled in from the exterior not the side. The "filler" of holes can be any of the five things listed at A29 to C29 and B30 and C30 (air, ABS plastic, aluminum, brass, lead). Filler #6 is anything of your choosing. Just find its density online and then enter it at D30 with ".00" before it. The example here is beryllium copper with a density of 8175 which I entered as .008175. The hole filler # (1-6) is to be entered at row 33. Some people like to fill holes to not lose any crankcase compression. Or if the setup is over-balanced then holes can be filled with steel or lead to correct that. I wouldn't fill a hole just for concern about crankcase compression because that affects engine power very little.  The remaining necessary data is the length of the holes (usually same as the width of the crank wheel), the distance from the hole center to the center of the crankshaft, and the degrees of the holes from the vertical (which goes through the conrod pin). Most holes are close to the con rod pin but if the holes are too big then you can counter that by having two holes at 180 degrees which would be on the opposite side of the crank than the con rod pin. If the ends of the con rod has oil holes or slots in it then you can add that info starting at H141.

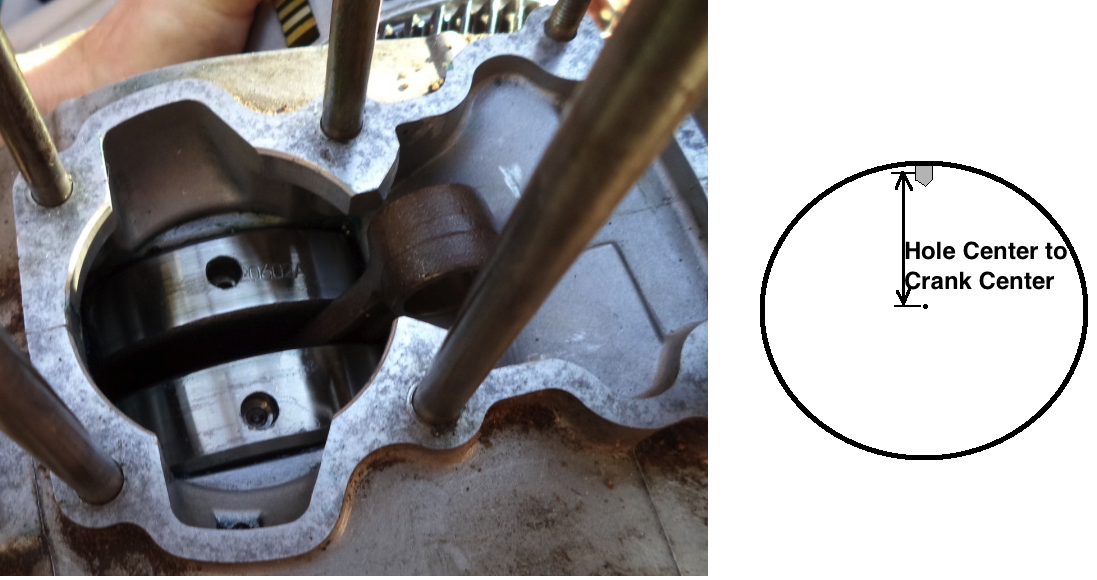

For most engines the main goal is to have the # at E45 as close to 0.97 as possible but if you just keep the engine pinned at top RPM then you can make it 1.0 instead. The max engine RPM at E2 is the maximum RPM that you normally use.  If you decide to drill holes into the outer part of the crank wheels, then to know how to account for the area of the drill bit tip/cone just divide the mm width of the bit by 10 and use that as the additional depth in the program, added to the depth of the shank. The "hole center to crank center" of row 36 is to be measured as shown in the drawing below. Measure to the middle depth of the shank. If you drill these holes then you have to do something to prevent any metal bits going down in the crank. It helps to use a magnet to accumulate the metal after drilling. Grind an X into the crank wheels with a rotary tool and cutting disk where you want each hole. That keeps the drill bit from wandering. You can start with a smaller carbide drill bit and then drill larger.

To change millimeters to inches just divide by 25.4, so that as an example 8.7mm divided by 25.4 is .342 inch which can then be translated to 16ths of an inch by multiplying by 16 which gives 5.5 which isn't a whole # so it has to be converted to 32nds which is 11/32" (multiplying both numbers by 2). So a 11/32" drill bit would work to drill a 8.7mm hole. Questions about each bit of data to be entered can often be answered by hovering the pointer over the description box. That will reveal the note I have saved that explains more. But if you still have questions after reviewing this page then contact me at 19jaguar75@gmail.com Here is a compete description of what is required for each data entry cell of the spreadsheet.

Here's my YouTube videos about crank balance: #1 #2 #3 #4 The last video explains how to figure out the equivalent balance holes for a crank with sculpted out areas instead of balance holes. The method and the graph is different in the video because that was made before my latest update but still it is worth watching. Some engines also have an extra balancer shaft which reduces the average radial force on the crankshaft by 50%. Here's two pictures of one:  Their weight being spread out reduces the outward force from what you could calculate it being if all of its weight contributed to the central outward force. I figured the % contributing to that force is 55% of the balancer weight (excluding the end pivots). That is what shows at E152. On the spreadsheet starting at row 141 is this section which is needed to help you find the center of gravity of the balancer and its weight. First you should weigh the whole thing and then find the weight of its end shafts. Put water into a cup that is level with the top when the shaft end is submersed. Use the skinniest cup available.  Then remove the shaft and measure how far down the water level now is. Enter the vessel inner diameter at E159 and the height change of the water at E161. The balancer weight without end shafts at E152 should be entered at E26. (Make sure E26 is 0 when working with a crank without an extra balance shaft.)  You'll need to glue something to the balancers flat surface which will extend away from it so you can hang a weight from it. Before glueing or taping the extender on then weigh it and enter its weight at E146. After it is attached then measure the two distances D1 and D2 to be entered at E142 and E144. Then add weights to the string/wire till the shaft will stay still without turning. Enter that weight in grams at E148. The calculated distance from shaft center to balancers center of gravity will appear at E155 which needs to be entered at E24. Below are radial force graphs, the first one being without a balancer. A balancer brings down the peak radial force and the difference between peaks. The last two are the best. So when analyzing for a crank with extra balancer you can only go by the graphs, not by the number at E46 and the Vector Ratio graph which happens after clicking the macro button. Mostly go by the 360 degree forces graph.  Also take note of the vertical and horizontal force #'s listed below the graph. Probably the best graph has these two values as low as possible and close to being the same.  Most typically the balancers are set up like this below when the counter balance holes in the crank wheels aren't big enough to counter balance the upper assembly weight:

HOME |